2/18/24

Today I begin a new series in the Montaigne Project that will take me a little over 200 years forward from Michel de Montaigne to the great 19th century novelist Marie-Henri Beyle, better known by his pen name Stendhal. Specifically, I will employ the write-as-I-read approach to Stendhal’s nonfiction book “De L’Amour.” I will do this without having read the book before, much as I first tackled Montaigne’s essays back in 2011.

I’m not a newcomer to Stendhal. I consider his novel “Le Rouge et Le Noir” to be a remarkable piece of dual writing – it’s both a historical novel written in and about it’s time, and a deeply insightful psychological exploration of these (mostly) rural French characters around 1830. It’s Stendahl’s uncanny ability to balance analysis and insight, satire and psychology that draws me to him. I think on some level I desire to think and write like him.

This is not a newfound desire. Over the past four years, I’ve taken two new swings at Montaigne, hoping to use his combination of introspection, skepticism and Stoicism to conquer some very strong feelings I was working my way through. It’s no news flash to anyone who read either my 2020-21 series of personal essays or my 2023 revival of the Montaigne Project (rewriting it all from start to finish) to say that I was dealing with quite a bit of in my life at both times. While both writing projects helped me work through strong feelings, the fact that neither project still resides on this website is evidence of how difficult it was for me to deal with the subjects that came up and how unwilling I am to let what I wrote day-to-day define me now.

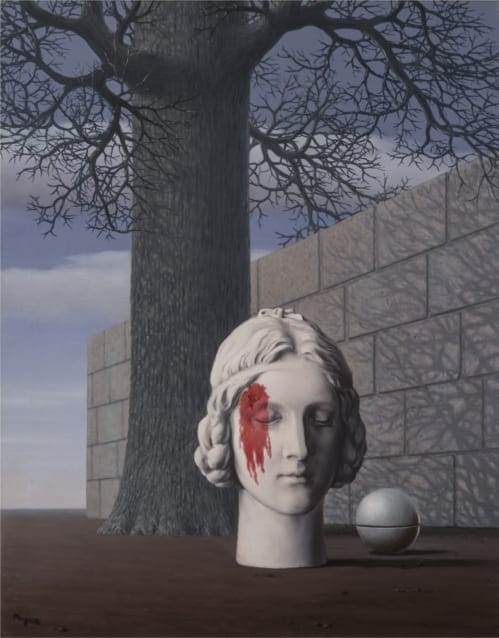

And yet, I feel uneasy about that absence. I have now twice aborted a project I still feel compelled to tackle. Perhaps Montaigne was the wrong frame for the issues I was dealing with. In addition, there was a problem of immediate feelings on the surface in both sets of essays. In each series, I was enmeshed in romantic feelings that were inexplicable to me – as if I’d entered a hall of mirrors. Writing was my attempt to escape that hall and make rational sense of it all. I honestly believed that I was facing not just an emotional challenge, but a vocational one as well – that it was time for me to come to terms with my own emotions and learn how to understand and communicate them as clearly as I could anything else.

These sets of essays found me trying to make sense of two different bouts of intense unrequited love. The first of those is well in the rear view mirror for me, and I can think about it without attaching any live feelings. The second is not quite in that completely safe place. Some days it feels resolved, but other days it creeps back in to disturb me. I know that I am not entirely healed from it because I still have no strong desire to enter into another romantic relationship, even though I occasionally become curious about women I know are interested in me, and from time to time check out dating apps so I can feel that purely contemporary brand of disinterest and disappointment while watching my money burn.

So I’m going to use Stendhal as my guide here and I’m not exactly sure what I’m getting myself into. But before doing that, I want to take a stab at connecting this work with Montaigne, because I do think there’s something unique about the French way of thinking that connects these projects in some way. What I don’t want to do, however, is to use Montaigne’s thoughts about love as a way into this discussion, because that’s a dead end. I admire many things about Michel de Montaigne, but his view of marriage, love, sex and basically anything that happens between men and women is not at all applicable to anything I experience in my life today, and I closed that avenue in my last series of essays.

Montaigne does have a great deal to say across his 107 essays about knowledge, thought, opinion, and theory. He mostly finds it all a grand waste of time. For this I jump right to the end of his essays, to “On Experience,” where he has his final word about the philosophers:

Go on then, just to see: get that fellow over there to tell you one of these days what notions and musings he stuffs into his head, for the sake of which he diverts his thoughts from a good meal and regrets the time spent eating it. You will find that no dish on your table tastes as insipid as that beautiful pabulum of his soul (as often as not it would be better if we fell fast asleep rather than stayed awake for what we do it for) and you will find that his arguments and concepts are not worth your rehashed leftovers. Even if they were the raptures of Archimedes, what does it matter?

There is something odd about this amusing little attack on intellectuals ... what exactly has Montaigne been doing in his essays if not sharing his notions and musings? His essays are not about his meals or exhaustive descriptions of other people’s salons ... Marcel Proust will pick up that calling in the early 20th century. No, Montaigne tries very hard across his essays to make sense of the life of the mind. But throughout, he remains skeptical – “what do I know” remains his calling card – and by the end of his project, he’s ready to call the entire intellectual enterprise something not worth exploring. He doesn’t believe human beings are capable of reaching ultimate truths, that everything related to the intellect is subject to skepticism and doubt.

Montaigne dies in 1592. Rene Descartes is born in 1596. And what Descartes does is accept this deep skepticism that Montaigne articulates, but reshapes it through something that comes to be called Systematic Doubt. American philosopher William Barrett beautifully describes this in his book “Irrational Man:"

(Descartes) proposes to reject all beliefs so long as they can in any way be doubted, to resist all temptations to say Yes until his understanding is convinced according to its own light; so he rejects belief in the existence of an external world, of minds other than his own, of his own body, of his memories and sensations. What he cannot doubt is his own consciousness, for to doubt is to be conscious, and therefore by doubting its existence he would affirm it. In the dark void in which Descartes hovered there shone only the light of his own mind. But before this certitude shone for him (and even after it, before he passed on to other truths), he was a nothingness, a negativity, existing outside of nature and history, for he had temporarily abolished all belief in a world of bodies and memories.

And so in this very brief historical span, we traverse from Montaigne’s highly humanistic and personal rejection of the intellect, to this Cartesian elevation of the mind above all else – so highly elevated that it might transcend anything we are capable of experiencing, rendering it all nothing. I would contend, that this is the central tension in all French thinking that extends all the way to present day.

Barrett, who I just mentioned above, makes the rather startling claim that Descartes has won this battle completely. He writes:

(Jean-Paul) Sartre is a Cartesian who has read Proust and Heidegger, and whose psychological explorations of man go far beyond those of the seventeenth-century philosopher; more important still, he is a Cartesian who has experienced war and terror in the modern world and who is therefore situated historically in an altogether different relation to the world. But a Cartesian he is, nonetheless, as perhaps no Frenchman – or no French thinker - can help being when the chips are really down.

Barrett can be excused for declaring Descartes the winner because he was writing in the 1950s and existentialism was the dominant philosophy of that time. But less than a decade later, France would produce Michel Foucault and Jacques Derrida, who would not only renew the challenge over what we really know, they will attempt to deconstruct the entirety of modern existence and see it all as a power struggle stacked in favor of dominant parties. But I really don’t want to go there, other than to say that Montaigne’s lighthearted skepticism lives on today, in far more ominous tones.

But since Barrett did bring up Marcel Proust, I want to bring him into the discussion now. Barrett sees Proust, who is a Frenchman after all, as someone not quite in the Cartesian camp. And in their introduction to Stendahl’s “De L’Amour,” Jean Stewart and B.C.J.G. Knight bring Proust into their examination of Stendahl’s subject as well.

Stewart and Knight say that the most famous feature of Stendhal’s book is the analysis of the power of the imagination in love “it’s ability to transfigure the image of the loved one – described in terms of the natural phenomenon of ‘crystallization.’” They note that this is not a subject that Stendhal invented, however:

But surely no one before Stendhal, and since Stendhal no one until Proust, has subjected it to such penetrating analysis without loss of feeling, admitting the illusion what still under its spell.

And then Stewart and Knight note a way that Stendhal anticipates Proust, in Chapter 15 of his book:

when he describes the curious ’blankness’ in which the lover’s heart is sometimes becalmed (what Proust later calls les intermittences du cœur.)

Aha ... now that is a subject I can explore before jumping into Stendhal. The “Intermittences of the Heart” sections of Proust’s masterpiece are some of his most insightful and beautiful thoughts. He coins this phrase early in Volume 4, “Sodom and Gomorrah.” Proust writes:

For the disturbances of memory are linked the intermittences of the heart. It is no doubt the existence of our body, similar for us to a vase in which our spirituality is enclosed, which induces us to suppose that all our inner goods, our past joys, all our sorrows, are perpetually in our possession. Perhaps this is as inaccurate as to believe that they escape or return. At all events, if they do remain inside us, it is for most of the time in an unknown domain where they are of no service to us, and where even the most ordinary of them are repressed by memories of a different order, which exclude all simultaneity with them in our consciousness. But if the framework of sensations in which they are preserved be recaptured, they have in their turn the same capacity to expel all that is incompatible with them, to install in us, on its own, the self that experienced them.

I don’t know how anyone else responds to that quote (which, by the way, is only a small part of one of Proust’s epic multi-page paragraphs) but I find it to be mind blowing. And he goes on here to relate it to a very touching remembrance of his grandmother and his deep feelings for her and how they were re-triggered in an instant. But what makes this novel great, and chilling in a way, is how Proust lets the idea sit for awhile, then brings it back in the end of this volume to describe events that are far less comforting to him.

A little background on the plot is in order: the book’s narrator Marcel is romantically obsessed by a woman named Albertine, an athletic, sociable young woman who completely confuses him. Sometimes she is very affectionate with Marcel, other times she’s distant. But Marcel notes that his feelings about her aren’t steady either – he sometimes questions whether he’s even attracted to her. Towards the end of this volume, Marcel has finally had enough and tells his mother that he’s fed up with Albertine and will not pursue her any more. Yet he still asks Albertine if she would alter her vacation plans and take a detour train ride with him home to Combray, which she agrees to do.

On this train ride, Albertine casually slips out information about some of the friends that she plans to see during this vacation, and all the puzzle pieces about her suddenly fall into place for Marcel ... he suddenly realizes that he’s become romantically obsessed with a lesbian.

It is often only for want of the creative spirit that we do not go far enough in suffering. And the most terrible reality brings us, at the same time as suffering, the joy of a beautiful discovery, for all that it does is to lend a new and explicit form to what we had long been turning over in our minds without suspecting it.

It’s that intermittence of the heart bursting into existence again. Marcel, being this perfectly drawn character stuck in between Descartes’ intellectualism and Montaigne’s presence, now faces a crisis. And what emerges is stunning insight:

the mistresses whom I have loved the most have never coincided with my love for them. This love was true, since I subordinated everything else to seeing them, to keeping them for myself alone, since I would sob if, one evening, I had waited for them. But they had the peculiar quality of arousing that love, of carrying it to a paroxysm, rather than of being the image of it. When I saw them, when I listened to them, I found nothing in them that might resemble my love or be able to explain it.

Or to put into Freudian psychoanalytic terms, Marcel so throughly projected his own ideal amorous feelings onto these women that they scarcely existed at all. They achieved this Cartesian nothingness because Marcel was playing out this love story that existed purely in his mind.

Marcel next notes that unrequited love brings out this hidden love creature inside us:

What a deceitful sense sight is! A human body, even when loved, as was that of Albertine, seems, from a few meters, a few centimeters away, distance from us. And the soul that belongs to it likewise. Except that, should something come violently to alter the position of that soul in relation to us, to show us that it loves other human beings and not ourselves, then, by the beating of our dislocated hearts, we feel that the cherished creature was not a few feet away, but inside us.

The all-too-human result of this turmoil is that Marcel sees his mother again that evening and instead of relating how he had just learned something about Albertine that validates his intuition and the thoughts he shared with his mother recently, Marcel begins to cry and expresses remorse for saying such terrible things about Albertine. His mother comforts him and says he said nothing terrible about her, he just related that she’s not the right woman for him. To which Marcel responds, closing volume 4 and setting up all kinds of misery for them both in the next two volumes “I absolutely must marry Albertine."

Somewhere Montaigne is smiling at all this, I assume. Cartesian consciousness may very well be proof of our existence, but what good is it when insight drives us to self destruction? Proust beautifully explains how this happens:

As though by an electric current that moves you, I have been shaken by my love affairs, I have lived them, I have felt them; never have I succeeded in seeing them or thinking them.

I can’t tell you how much comfort that line gives me. If Marcel Proust was incapable of seeing or thinking through his romantic feelings, why on earth should I beat myself up for struggling so mightily with my own? It’s a struggle Stendhal felt as well. As Stewart and Knight note in their introduction:

(De l’Amour) displays the two conflicting sides of his nature – the deeply sensitive and the cooly analytical. These aspects are indeed present in everything he wrote, but in the great novels they are fused miraculously, whereas in De l’Amour they are in somewhat uneasy juxtaposition. The effort he made to control his feeling self was too great; these experiences were too close, too traumatic for lucidity to prevail. Emotion was hardly ‘recollected in tranquility’; even when he was correcting the proofs of De l’Amour he wept: ‘I nearly went crazy,’ he said in Souvenirs d’Egotisme.

Well, I am certainly hoping to neither weep nor go crazy during this project, but I enter it with satisfaction that Stendhal was not a master of his emotional self either. We’ll see how this goes – wish me luck.